Textmining

Introduction to Text Mining

“Text Mining is the discovery by computer of new, previously unknown information, by automatically extracting information from different written resources… The difference between regular data mining and text mining is that in text mining the patterns are extracted from natural language text rather than from structured databases of facts.” - from What is Text Mining? by Marti Hearst

Why text mining? Automated search strategies can provide an overview of patterns and tendencies in large volumes of text. This may provide insight that would otherwise be difficult to achieve, time-consuming or both through conventional qualitative methods.

Types of text mining and digital analysis of text

Tools and software bundles for text mining

Text mining requires readable big data - a note on the value of platforms such as NLTK and DH-Lab.

Quick look at DH-Lab Tools and Voyant Tools - option to revert to these during the course.

More and more archives have their own tools to text mine their collections, with or without subscription. Some familiarity with programming is often necessary, typically in Python.

Learning a programming language is like learning any new language. It requires copying, repeating, using a dictionary, practicing, learning enough of the “grammar” of the language to detect typos and mistakes.

- Learn how to look things up (textbooks, published tutorials, useful resources online, forums).

Learning goals:

Get a sense of how the Python program works (the math behind it with strings and loops).

Get a feel for how Python code can be used to text mine.

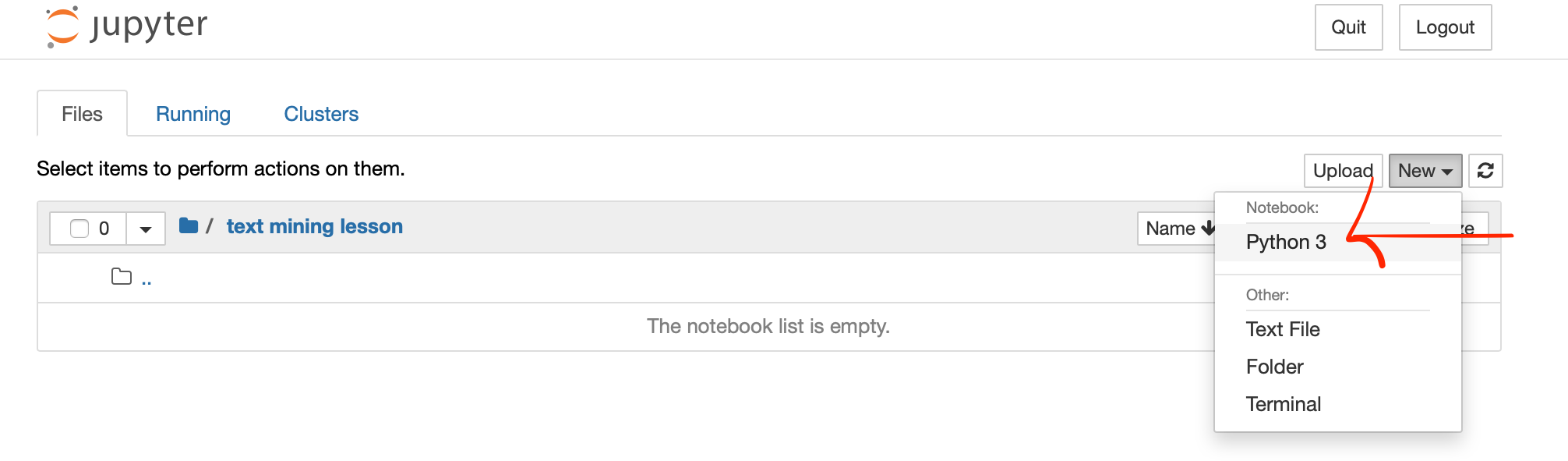

Introduction to Jupyter Notebook

This course teaches programming in Python to text mine. It uses the application Jupyter Notebook from the navigator Anaconda as the environment for Python. The Natural Language Toolkit, NLTK, a leading platform for building Python programs to work with human language data (“natural language processing” or NLP), also comes with Anaconda as one of many packages and libraries you can select to install and run in Jupyter Notebook, and will be used in this course. Python, Jupyter, and NLTK are open source and free.

Download and install Anaconda (free and easy to install). Open Anaconda, launch Jupyter Notebook from Anaconda, and select new Notebook in Python.

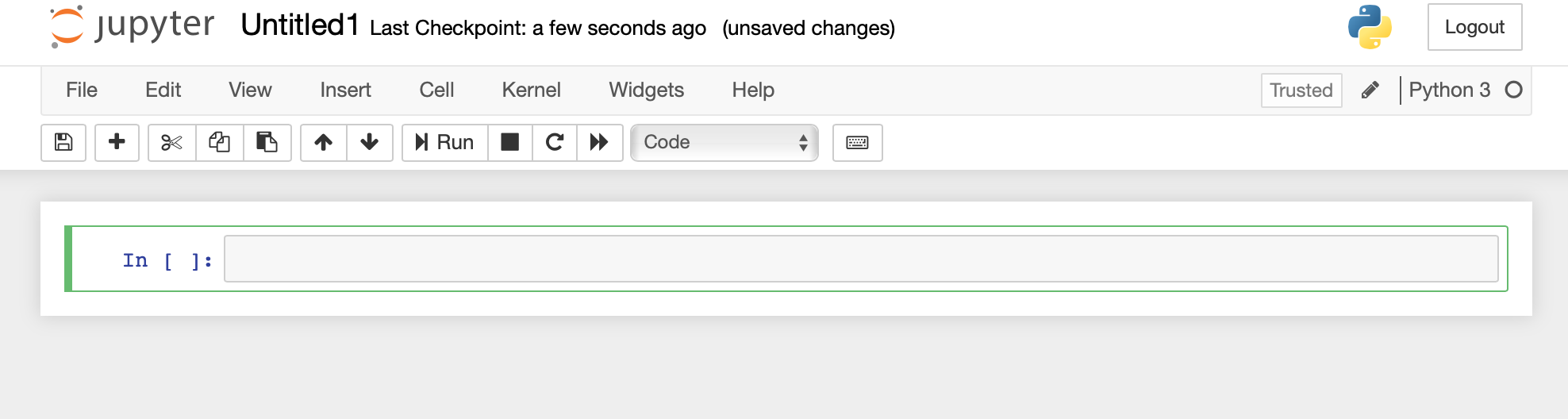

Once the new notebook opens you can give it a name by changing the word “Untitled” in the first line of the new notebook that opens up. You can see and change the location for where the notebook is saved in the browser window, see also the finder menu.

You will see the first cell in your new notebook. You can enter python code into this cell and press “Run” as long as it is marked as “Code” in the menu at the top of your notebook. This will run your code and you will see any output created by the code immediately below it.

Introduction to Python Fundamentals

Keypoints:

- Use

name = valueto assign a value to a variable with a specific name in order to record it in memory - Use the

print(variable)function to print the value of the variable - Create list by giving it different values (

list-name['value1','value2','value3']) and use a for loop to iterate through each value of the list

Recommended textbooks

Please confer with the recommended textsbooks for this section, which will give you a basic introductory understanding of the Python programming language and its logic, and which is important for understanding all the steps that follow through the course. The recommended textbooks are: Natural Language Processing with Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit and Humanities Data Analysis: Case Studies with Python. The first chapters have good introductions: “Language Processing and Python” and “What you should know” on variables, strings, loops, lists, dictionaries, conditional expressions (if, elif, else), and reading files.

Printing text

We first want to test that Python works by asking it to print a string, so type print("Hello World") into the next Jupyter Notebook cell as shown below and run it as code.

print("Hello World")

Hello World

Variables and how to assign them

In Python, you can assign information to variables. A variable is a memory location used to hold data which has a name associated with it. You can think of it like a box which can contain information and which also has a name, so you can refer to it in code.

For example we can put the string (sequence of characters) “text mining” into the box named “text”.

We do that by assigning the string to the variable named text. When assigning variables in python, the name of the variable is on the left followed by an equal sign and the value of the variable, as follows:

text = "Text Mining"

You can see the content of the variable (what’s in the box) by printing the value of it using the print() function and the variable name as shown:

print(text)

Text Mining

In addition to strings we can assign other data types such as numbers and floats to variables.

text = "Text Mining" # An example of a string

number = 42 # An example of an integer

pi_value = 3.1415 # An example of a float (a number with a decimal)

In this lesson we will be concentrating mainly on strings.

Note

Whenever something is followed by the

#sign in Python code then it is a comment and not part of the code. Comments are used to explain the code but are not needed to run it.

A list

Data can be grouped together in an ordered way using a list, a sequence of items such as a string, an integer, a float. Lists are very common data structures used in Python, for example to represent text.

In the following example the list named “sentence” stores all the words and punctuation of the sentence “This is an example sentence.”

Lists are created by typing comma separated values inside square brackets. You can print out all elements in the list.

sentence = ['Just', 'think', 'happy','thoughts', 'and', 'you', '’ll', 'smile', '.']

print(sentence) # print all elements

['Just', 'think', 'happy', 'thoughts', 'and', 'you', '’ll', 'smile', '.']

The list holds an ordered sequence of elements (in this case words or punctuation) and each element can be accessed using its index or position in the list. To do that you need to specify the index.

Note

Python indexes start with 0 instead of 1. So the first element in the list is called using a 0 in square brackets after the name of the list

print(sentence[0]) # print the first element

Just

You can also print a slice of the list (e.g. the first two elements of the list):

sentence[0:2]

['Just', 'think']

You can delete an item in the list by using the pop() function specifying the index of the element (unless you want to remove the last one).

sentence.pop(7)

print(sentence) # prints the entire list at once

['Just', 'think', 'happy', 'thoughts', 'and', 'you', '’ll', '.']

Items can be added to a list either by inserting them at a specific position (index) or by appending them to the end of the list.

sentence.insert(7,'fly')

print(sentence)

sentence.append('[J.B. Barrie]')

print(sentence)

['Just', 'think', 'happy', 'thoughts', 'and', 'you', '’ll', 'fly', '.']

['Just', 'think', 'happy', 'thoughts', 'and', 'you', '’ll', 'fly', '.', '[J.B. Barrie]']

A for loop

A for loop can be used to access the elements in a list one at a time.

The syntax for a for loop starts with for x in y: where y is the thing you want to loop through (in our case a list) and x is a new variable which each element of y is assigned to while looping. So when looping, x keeps getting overwritten by the next element of y until the end of y is reached.

The code after the initial line then specifies what is to be done with each element of y. This needs to be indented using a tab so that Python knows the instructions that follow need to be executed for each element.

For example, you can loop through the sentence list by assigning each element to the word variable and then print each element by calling the print() function:

for word in sentence:

print(word) # prints each element of the list one after the other

Just

think

happy

thoughts

and

you

’ll

fly

.

[J.B. Barrie]

if/elif/else statements

An if/elif/else statement can be used to condition some code on something being true or false. This is useful when wanting to only run some code if a specific condition is met or for running different bits of code depending on what condition is met.

If the test that follows the statement is true, then its body (i.e., the lines indented underneath it) are executed. If the test is false then the indented code is not executed and the programme continues.

In the following example, the code specifies that if the sentence list contains 5 elements then print text to confirm that, else if the list contains more than 5 elements then print text to say it does. If neither of those two conditions are true (else) which means the sentence list contains less than 5 elements, then print something saying that is the case. Finally print the entire list to show which elements it contains. The last line of code is not indented as it is supposed to run independent of the if/elif/else statements.

We use the len() function to count the length of the list which returns an integer and we also use operators as part of the tests (== for is equal to and > for is greater than).

if len(sentence) == 5:

print("The sentence list contains 5 tokens.")

elif len(sentence) > 5:

print("The sentence list contains more than 5 tokens.")

else:

print("The sentence list contains less than 5 tokens.")

print(sentence)

The sentence list contains more than 5 tokens.

['Just', 'think', 'happy', 'thoughts', 'and', 'you', '’ll', 'fly', '.', '[J.B. Barrie]']

Dictionary

A dictionary works a lot like a list but it contains ‘key/value’ pairs. A key acts as a name for a single or a set of values in the dictionary.

In the example below the values are integers (e.g. counts). So a dictionary could be used to store the number of times (the value) a word (the key) occurs in a text.

pets = {'cats':45, 'dogs':24, 'mice':33}

print(pets['cats']) # prints the value of the key 'cats'

45

We can use a for loop to print the keys and values of a dictionary:

for key, value in pets.items():

print(key, value)

cats 45

dogs 24

mice 33

Task 1: Printing text

Print a bit of text of your choice using print()

Key

print("Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall")Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall

Task 2: Create a list

Create a list containing different first names, iterate through them

Key

names = ['Mary', 'John', 'Bob'] for name in names: print(name)Mary John Bob

Tokenising Text

Keypoints:

- Tokenisation means to split a string into separate words and punctuation, for example to be able to count them.

- Text can be tokenised using a tokeniser, e.g. the punkt tokeniser in NLTK.

But first … importing packages

Python has a selection of pre-written code that can be used. These come as in built functions and a library of packages of modules. We have already used the in-built function print(). In-built functions are available as soon as you start python. There is also a (software) library of modules that contain other functions, but these modules need to be imported.

For this course we need to import a few libraries into Python, including the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). To do this, we need to use the import command and run import nltk. We will also use numpy to represent information in arrays and matrices, string to process some strings, and matplotlib to visualise the output.

If there is a problem importing any of these modules you may need to revisit the appropriate install above.

import nltk

import numpy

import string

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Tokenising a string

In order to process text we need to break it down into tokens. As we explained at the start, a token is a letter, word, number, or punctuation which is contained in a string.

To tokenise we first need to import the word_tokenize method from the tokenize package from NLTK which allows us to do this without writing the code ourselves.

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

We will also download a specific tokeniser that NLTK uses as default. There are different ways of tokenising text and today we will use NLTK’s in-built punkt tokeniser by calling:

nltk.download('punkt')

Now we can assign text as a string variable and tokenise it. We will save the tokenised output in a list using the humpty_tokens variable. We can inspect this list by inspecting the humpty_tokens variable.

humpty_string = "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall; All the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't put Humpty together again."

humpty_tokens = word_tokenize(humpty_string)

# Show first 10 entries of the tokens list

humpty_tokens[0:10]

['Humpty', 'Dumpty', 'sat', 'on', 'a', 'wall', ',', 'Humpty', 'Dumpty', 'had']

As you can see, some of the words are uppercase and some are lowercase. To further analyse the data, for example counting the occurrences of a word, we need to normalise the data and make it all lowercase.

You can lowercase the strings in the list by going through it and calling the .lower() method on each entry. You can do this by using a for loop to loop through each word in the list.

lower_humpty_tokens = [word.lower() for word in humpty_tokens]

# Show first 10 entries of the lowercased tokens list

lower_humpty_tokens[0:6]

['humpty', 'dumpty', 'sat', 'on', 'a', 'wall']

Task: Printing token in list

Print the 13th token of the nursery rhyme (remember that a list index starts with 0).

Key

print(lower_humpty_tokens[12])fall

Data Preparation

Keypoints:

- To open and read a file on your computer, the

open()andread()functions can be used. - To read an entire collection of text files you can use the

PlaintextCorpusReaderclass provided by NLTK and itswords()function to extract all the words from the text in the collection.

Text data comes in different formats that must be parsed into plain text for Python to read it. In this part of the lesson we will show you how to load a single document and how to load the text of an entire corpus into Python for further analysis. For more on corpora you can access and preprocessing of data, we recommend the chapters on accessing text corpora and processing raw text in the NLKT textbook. You may also want to consult the first couple of chapters in the textbook Humanities Data Danalysis: Case Studies with Python regarding data formats and preprocesing.

Download some data

Firstly, please download a dataset and make a note of where it is saved on your computer. We need the path to dataset in order to load and read it for further processing.

We will use the Medical History of British India collection provided by the National Libarry of Scotland as an example:

This dataset forms the first half of the Medical History of British India collection, which itself is part of the broader India Papers collection held by the Library. A Medical History of British India consists of official publications varying from short reports to multi-volume histories related to disease, public health and medical research between circa 1850 to 1950. These are historical sources for a period which witnessed the transition from a humoral to a biochemical tradition, which was based on laboratorial science and document the important breakthroughs in bacteriology, parasitology and the developments of vaccines in a colonial context.

This collection has been made available as part of NLS’s DataFoundry platform which provides access to a number of their digitised collections.

We are only interested in the text the Medical History of British India collection for this course so at the bottom of the website, download the “Just the text” data or download it directly here.

Note that this dataset requires approx. 120 MB of free file space on your computer once it has been unzipped. Most computers automatically uncompress .zip files as the one you have downloaded. If your computer does not do that then right-click on the file and click on uncompress or unzip.

You should be left with a folder called nls-text-indiaPapers containing all the .txt files for this collection. Please check that you have that on your computer and find out what its path is. In my case it is /Users/balex/Downloads/nls-text-indiaPapers/.

Loading and tokenising a single document

You can use the open() function to open one of the files in the Medical History of British India corpus. You need to specify the path to a file in the downloaded dataset and the mode of opening it (‘r’ for read). The path will be different to the one below depending on where you saved the data on your computer.

The read() function is used to read the file. The file’s content (the text) is then stored as a string variable called india_raw.

You can then tokenise the text and convert it to lowercase. You can check it has worked by printing out a slice of the list lower_india_tokens.

file = open('/Users/annesabo/Downloads/nls-text-indiaPapers/74457530.txt','r') # replace the path with the one on your computer

india_raw = file.read()

india_tokens = word_tokenize(india_raw)

lower_india_tokens = [word.lower() for word in india_tokens]

lower_india_tokens[0:10]

['no', '.', '1111', '(', 'sanitary', ')', ',', 'dated', 'ootacamund', ',']

Loading and tokenising a corpus

We can do the same for an entire collection of documents (a corpus). Here we choose a collection of raw text documents in a given directory. We will use the entire Medical History of British India collection as our dataset.

To read the text files in this collection we can use the PlaintextCorpusReader class provided in the corpus package of NLTK. You need to specify the collection directory name and a wildcard for which files to read in the directory (e.g. .* for all files) and the text encoding of the files (in this case latin1). Using the words() method provided by NLTK, the text is automatically tokenised and stored in a list of words. As before, we can then lowercase the words in the list.

from nltk.corpus import PlaintextCorpusReader

corpus_root = '/Users/annesabo/Downloads/nls-text-indiaPapers/'

wordlists = PlaintextCorpusReader(corpus_root, '.*', encoding='latin1')

corpus_tokens = wordlists.words()

print(corpus_tokens[:10])

['No', '.', '1111', '(', 'Sanitary', '),', 'dated', 'Ootacamund', ',', 'the']

lower_corpus_tokens = [str(word).lower() for word in corpus_tokens]

lower_corpus_tokens[0:10]

['no', '.', '1111', '(', 'sanitary', '),', 'dated', 'ootacamund', ',', 'the']

Task 1: Print slice of tokens in list

Print out a larger slice of the list of tokens in the Medical History of British India collection, e.g. the first 30 tokens.

Key

print(corpus_tokens[:30])

Task 2: Print slice of lowercase tokens in list

Print out the same slice but for the lower-cased version.

Key

print(lower_corpus_tokens[0:30])

Concordance Analysis or Keywords in Context (KWIC)

Keypoints:

- A concordance list is a list of all contexts in which a particular token appears in a corpus or text.

- A concordance list can be created using the

concordance()method of theText` class in NLTK.

Next, we will display concordances for a particular token, i.e. all contexts a particular token appears in. We can do this by first importing the Text class, a wrapper which supports exploration and analysis through a variety of analyses, including by concordancing. See full description of Text class functionality at NLTK. The concordance list of a token is displayed using the concordance() method as shown below.

from nltk.text import Text

t = Text(lower_india_tokens)

t.concordance('woman')

Displaying 20 of 20 matches:

s of age , a sweeper , who married a woman who had leprosy , and at the age of

e of sitabu , aged 40 , a muhammadan woman . her grand- father and father were

ung man deliberately married a leper woman , and became himself a leper at the

contrary . in no . 6 a man marries a woman whose grandfather and father had bee

lepers . in no . 10 a man marries a woman whose father had died of leprosy . i

applies to these cases . in no . 2 a woman marries a man whose father and elder

n in the case of a man who marries a woman of notoriously leper family . in no

toriously leper family . in no . 5 a woman marries a man whose elder brother wa

d continued to cohabit with a native woman after she had been attacked with lep

isen from intermarriage of a man and woman in both of whom leprosy was heredita

s a leper ; he is now married to the woman , and they both live in the asylum .

een accompanied by a healthy looking woman , and by this means , although all h

editary transmission . in one case a woman got the disease about two years afte

passed their thirtieth year , one a woman about 25 years of age , and the seve

fracture of femur in middle third . woman well nourished and skin healthy , no

; had a brother with same disease . woman recovered and able to move about ; o

re or less related to each other . a woman got leprosy first from a leprous hus

s village assured me that before the woman returned home after her husband 's d

against it . this case was that of a woman with two leprous children , aged abo

ions had been lepers , who married a woman with tubercular leprosy , he being a

In the output for the next bit of code which creates a concordance list for the word “he”, we can see that there are many more results in the list than displayed on screen (Displaying 25 of 170 matches). The concordance() method only prints the first 25 results by default (or less if there are less).

t = Text(lower_india_tokens)

t.concordance('he')

Displaying 25 of 170 matches:

leprosy treated by gurjun oil , which he was able to watch for a length of tim

diminished . during these two months he gained three pounds in weight , which

does not seem much , considering that he did no work and was fairly well fed o

se from jail on the 23rd january 1876 he was again suffering from the sores th

n 5th and died on 20th october 1875 . he was seriously ill when he was brought

ober 1875 . he was seriously ill when he was brought to the hospital , and cou

itted on the 8th september 1875 , and he went home of his own accord on 20th d

is own accord on 20th december 1875 . he was much improved under treat- ment b

evalence of leprosy in the district , he had had but very few opportunities of

even half this number . the natives , he says , call every chronic skin diseas

in the legs , the feet and the ears . he has perfect taste , hearing , sight a

te laboured under it . the leper says he was quite free from leprosy until he

he was quite free from leprosy until he associated with this man and took din

prosy of 15 years ' standing . states he had first gonorrha , then syphillis ,

been affected 6 years ; was well when he married . had two children who died ,

ve of the territory beyond the hubb . he had lost some parts of his hands and

feet previous to his incarceration . he was treated with large doses of iodid

ease be removed . dr. bloomfield says he sent two interesting specimens of thi

ant medical college museum , but that he never heard of them after , nor did h

e never heard of them after , nor did he discover them in the museum when he v

d he discover them in the museum when he visited it afterwards . should the di

er and elder sister were lepers , and he himself became a leper at 30 years of

. his elder brother was a leper , and he himself became a leper at 32 . his wi

one year after she was affected , and he suffered from leprosy . no . 7.-the c

ied . afterwards , at the age of 43 , he him- self was attacked with leprosy .

You can specify the number of lines using an additional lines parameter, e.g.:

t.concordance('he',lines=170)

Task: Create a new concordance list

Create a concordance list for a different search term, e.g. the word “great” or choose your own.

Key

t.concordance('great')

Searching Text with Regular Expressions

Keypoints:

- To search for tokens in text using regular expressions you need the

remodule and itssearchfunction. - To learn how to construct regular expressions. E.g. you can use a wildcard

*or you can use a range of letters, e.g.[ae](for a or e),[a-z](for a to z), or numbers, e.g.[0-9](for all single digits) etc. Regular expressions can be very powerful if used correctly. To find all mentions of the wordswomanorwomenyou need to use the following regular expressionwom[ae]n.

This section provides a taster to the use of regular expression searching. For a more detailed overview and use of regular expressions, please refer to the chapter on Regular Expressions for Detecting Word Patterns in the NLKT textbook, as well as the Programming Historian lesson Understanding Regular Expressions.

You may want to look for the word “women” as well a “woman” in a corpus simultaneously, to find out how many times they occur. You would do this using regular expressions. Regular expressions define a search term that can have some variety in it. To use regular expression search in Python, you first need to import the re module.

import re

The next line is a bit more complex combining a for loop and and an if statement so let’s explain this in a bit more detail.

The code first goes through each element in the lower_india_tokens list using a for loop and assigning each element in that list to the variablew. The if statement then specifies to only return true if the strings assigned to w matches “woman” or “women”. If that is the case then the word is added to the womaen_strings list.

The regular expression search string ^wom[ae]n$ contains square brackets to indicate that the letter to match could be “a” or “e” (so either woman or women). ^ means start of string and $ means end of string, so the search is for the exact tokens “women” or “woman” but not for words containing them.

You can see all the strings found in the corpus assigned to the womaen_strings list by printing it.

womaen_strings=[w for w in lower_india_tokens if re.search('^wom[ae]n$', w)]

print(womaen_strings)

['women', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'women', 'woman', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'women']

You can see how the search results change if you remove the ^ and $ characters from the regular expression.

Now that the results are stored in a list you can count them. We will see how to do that later on.

womaen_strings=[w for w in lower_india_tokens if re.search('wom[ae]n', w)]

print(womaen_strings)

['women', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'women', 'woman', 'women', 'washerwoman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'women', 'woman', 'woman', 'women', 'women', 'women']

Regural expressions can be very specific and we will not cover them in detail here but they are very powerful to carry out complex searches, e.g. find all tokens starting with a and are 12 characters long (. means a character). Or find all tokens which are 13 characters long but that do not start with a lower case letter ([^a-z] means not the letters a-z).

[w for w in lower_india_tokens if re.search('^a............$', w)]

['antiscorbutic',

'approximately',

'approximately',

'agriculturist',

'ages.-chiefly',

'approximately',

'accommodation']

[w for w in lower_india_tokens if re.search('^[^a-z]............$', w)]

['24-pergunnahs',

'19.-commenced',

'24-pergunuahs',

'24-pergunnahs',

'24-pergunnahs',

'1875.-patches']

Task: Search for specific tokens using regular expressions

Search for all tokens starting with the string “man” or “men”

Key

maen_strings=[w for w in lower_india_tokens if re.search('^m[ae]n', w)] print(maen_strings)

Counting Tokens in Text

Keypoints:

- To count tokens, one can make use of NLTK’s

FreqDistclass from theprobabilitypackage. TheN()method can then be used to count how many tokens a text or corpus contains. - Counts for a specific token can be obtained using

fdist[\"token\"].

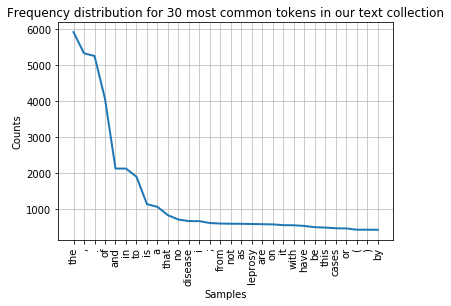

You can also do other useful things like count the number of tokens in a text, determine the number and percentage count of particular tokens and plot the count distributions as a graph. To do this we have to import the FreqDist class from the NLTK probability package. When calling this class, a list of tokens from a text or corpus needs to be specified as a parameter in brackets.

from nltk.probability import FreqDist

fdist = FreqDist(lower_india_tokens)

fdist

FreqDist({'the': 5923, ',': 5332, '.': 5258, 'of': 4062, 'and': 2118, 'in': 2117, 'to': 1891, 'is': 1124, 'a': 1049, 'that': 816, ...})

The results show the top most frequent tokens and their frequency count.

We can count the total number of tokens in a corpus using the N() method:

fdist.N()

93571

And count the number of times a token appears in a corpus:

fdist['she']

26

We can also determine the relative frequency of a token in a corpus, so what % of the corpus a term is:

fdist.freq('she')

0.0002778638680787851

If you have a list of tokens created using regular expression matching as in the previous section and you’d like to count them then you can also simply count the length of the list:

len(womaen_strings)

43

Frequency counts of tokens are useful to compare different corpora in terms of occurrences of different words or expressions, for example in order to see if a word appears a lot rarer in one corpus versus another. Counts of tokens, documents and a entire corpus can also be used to compute simple pairwise document similarity of two documents.

Task: Count the frequency of a particular token.

Change the word “she” to something else to see how the frequency changes.

Key

fdist.freq('he')

Visualising Frequency Distributions of Tokens in Text

Keypoints:

- A frequency distribution can be created using the

plot()method. - We can clean data by removing stopwords and other types of tokens from the text.

- A word cloud can be used to visualise tokens in text and their frequency in a different way.

Graph

The plot() method can be called to draw the frequency distribution as a graph for the most common tokens in the text.

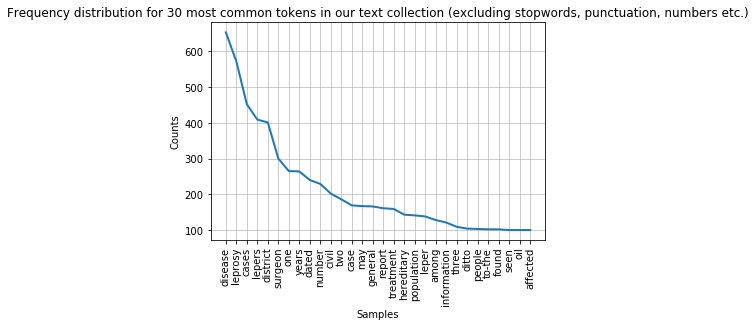

fdist.plot(30,title='Frequency distribution for 30 most common tokens in our text collection')

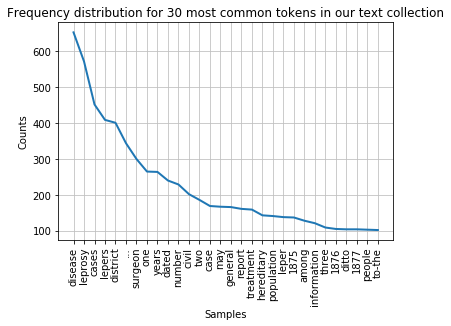

You can see that the distribution contains a lot of non-content words like “the”, “of”, “and” etc. (we call these stop words) and punctuation. We can remove them before drawing the graph. We need to import stopwords from the corpus package to do this. The list of stop words is combined with a list of punctuation and a list of single digits using + signs into a new list of items to be ignored.

nltk.download('stopwords')

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

remove_these = set(stopwords.words('english') + list(string.punctuation) + list(string.digits))

filtered_text = [w for w in lower_india_tokens if not w in remove_these]

fdist_filtered = FreqDist(filtered_text)

fdist_filtered.plot(30,title='Frequency distribution for 30 most common tokens in our text collection (excluding stopwords and punctuation)')

Note

While it makes sense to remove stop words for this type of frequency analyis it essential to keep them in the data for other text analysis tasks. Retaining the original text is crucial, for example, when deriving part-of-speech tags of a text or for recognising names in a text. We will look at these types of text processing later in this course.

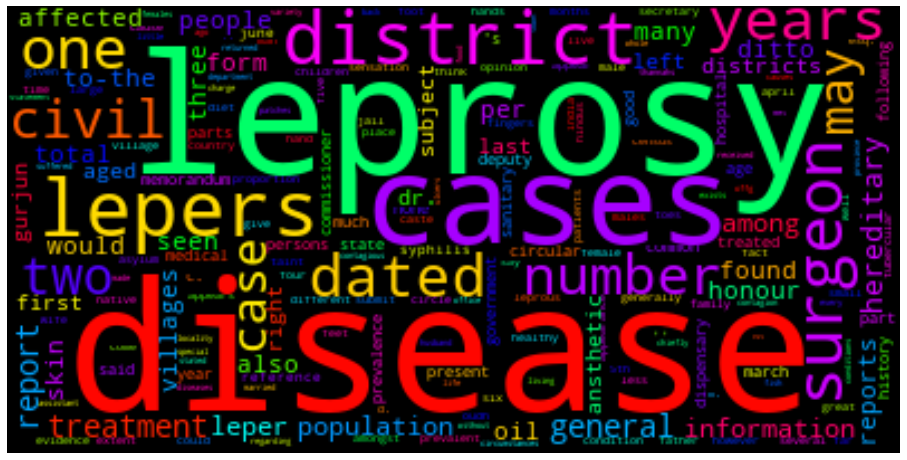

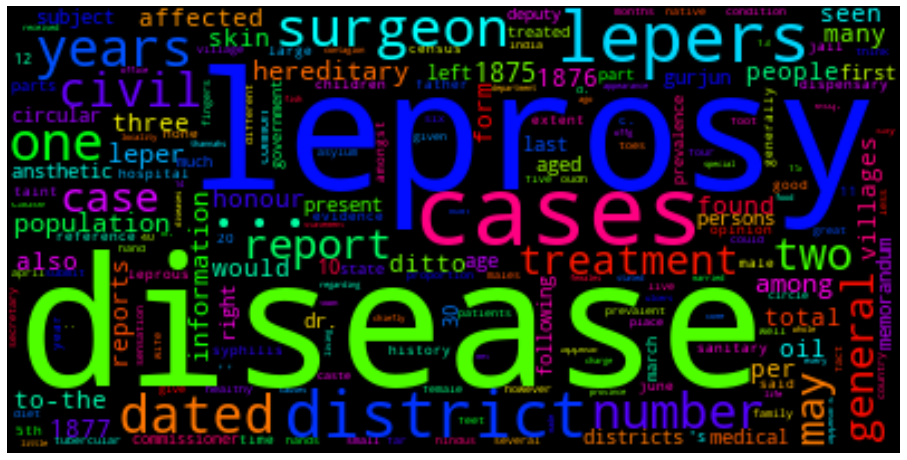

Word cloud

We can also present the filtered tokens as a word cloud. This allows us the have an overview of the corpus using the WordCloud( ).generate_from_frequencies() method. The input to this method is a frequency dictionary of all tokens and their counts in the text. This needs to be created first by importing the Counter package in python and creating a dictionary using the filtered_text variable as input.

We generate the WordCloud using the frequency dictionary and plot the figure to size. We can show the plot using plt.show().

from collections import Counter

dictionary=Counter(filtered_text)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wordcloud import WordCloud

cloud = WordCloud(max_font_size=80,colormap="hsv").generate_from_frequencies(dictionary)

plt.figure(figsize=(16,12))

plt.imshow(cloud, interpolation='bilinear')

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

Task 1: Filter the frequency distribution further

Change the last frequency distribution plot to not show any the following strings: “…”, “1876”, “1877”, “one”, “two”, “three”. Consider adding them to the

remove_theselist. Hint: You can create a list of strings of all numbers between 0 and 10000000 by callinglist(map(str, range(0,1000000)))Key

numbers=list(map(str, range(0,1000000))) otherTokens=["..."] remove_these = set(stopwords.words('english') + list(string.punctuation) + numbers + otherTokens) filtered_text = [w for w in lower_india_tokens if not w in remove_these] fdist_filtered = FreqDist(filtered_text) fdist_filtered.plot(30,title='Frequency distribution for 30 most common tokens in our text collection (excluding stopwords, punctuation, numbers etc.)')

Task 2: Redraw word cloud

Redraw the word cloud with the updated

filtered_textvariable (after removing the strings in Task 1).Key

dictionary=Counter(filtered_text) import matplotlib.pyplot as plt from wordcloud import WordCloud cloud = WordCloud(max_font_size=80,colormap="hsv").generate_from_frequencies(dictionary) plt.figure(figsize=(16,12)) plt.imshow(cloud, interpolation='bilinear') plt.axis('off') plt.show()

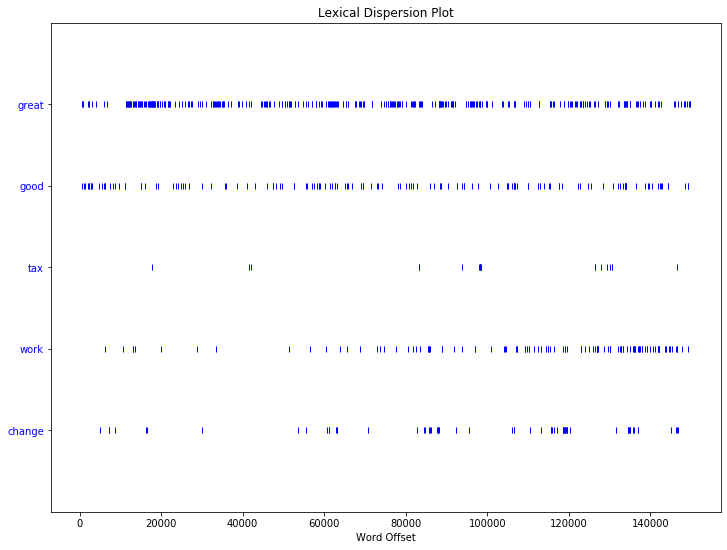

Lexical Dispersion Plot

Keypoints:

- Lexical dispersion is a visualisation that allows us to see where a particular term appears across a document or set of documents.

- We can use NLTK’s

dispersion_plotfor this.

We can plot lexical dispersion of particular tokens. Lexical dispersion is a measure of how frequently a word appears across the parts of a corpus. This plot notes the occurrences of a word and how many words from the beginning of the corpus it appears (word offsets). This is particularly useful for a corpus that covers a longer time period and for which you want to analyse how specific terms were used more or less frequently over time.

To create a lexical disperson plot, you will first load and import a different corpus, the inaugural corpus which are all US Presidential Inaugural Addresses and which are provided with NLTK.

nltk.download('inaugural')

from nltk.corpus import inaugural

from nltk.text import Text

inaugural_tokens=inaugural.words()

inaugural_texts = Text(inaugural_tokens)

[nltk_data] Downloading package inaugural to /Users/<USERNAME>/nltk_data...

[nltk_data] Package inaugural is already up-to-date!

To create the lexical dispersion plot for this corpus you also need to load dispersion_plot from the nltk.draw.dispersion package. You can then call the dispersion_plot method given a set of parameters, including the target words you want to plot across the corpus, whether this should be done case-sensitively, and specifying the title of the plot.

from nltk.draw.dispersion import dispersion_plot

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 9)) # command used to increase the size of the plot using width and hight specifications

targets=['great','good','tax','work','change']

dispersion_plot(inaugural_texts, targets)

Task: Create another lexical dispersion plot for this corpus to see how frequently words such as citizens, democracy, freedom, duties, and America appear across the inaugural addresses.

Key

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 9)) targets=['citizens', 'democracy', 'freedom', 'duties', 'America'] dispersion_plot(inaugural_texts, targets)

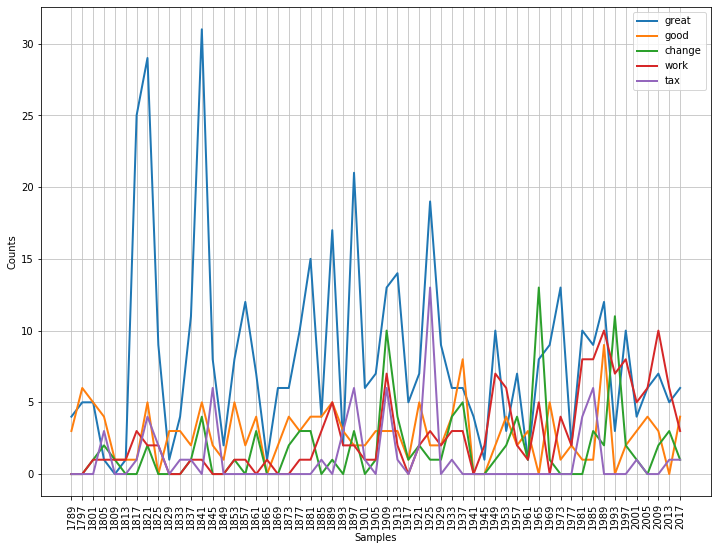

Plotting Frequency over Time

Keypoints:

- We can extract the terms and the years from the files using NLTK’s

ConditionalFreqDistclass from thenltk.probabilitypackage. - We can plot these on a graph to visualise how the use changes over time.

Similarly to lexical dispersion, you can also plot frequency of terms over time. This is similarly to the Google n-gram visualisation for the Google Books corpus but we will show you how to do something similar for your own corpus, such as the inaugural corpus.

You first need to import NLTK’s ConditionalFreqDist class from the nltk.probability package. To generate the graph, you have to specify the list of words to be plotted (see targets) and the x-axis labels, in this case the year the inaugural was held. The numbers for these years appear, fittingly, in the filename for each speech. We ask to see the fileids, the file identifiers in the inaugural corpus:

inaugural.fileids()

[‘1789-Washington.txt’, ‘1793-Washington.txt’, ‘1797-Adams.txt’, …]

Notice that the year of each inaugural speech appears at the start of each filename. To get the year out of the filename, we extract the first four characters: fileid[:4].

[fileid[:4] for fileid in inaugural.fileids()]

[‘1789’, ‘1793’, ‘1797’, ‘1801’, ‘1805’, ‘1809’, ‘1813’, ‘1817’, ‘1821’, …]

The plot is created by:

- looping through each file (speech)

- then looping through each word in each speech

- then looping through the list of specified target words and

- checking if each target word matches the start of each word in the speeches (after being lower-cased).

The ConditionalFreqDist object (cfd) stores the number of times each of the target words appear in the each of the speaches and the plot() method is used to visualise the graph.

from nltk.probability import ConditionalFreqDist

# type this to set the figure size

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12, 9)

targets=['great','good','tax','work','change', 'wom[ae]n']

cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist((target, fileid[:4])

for fileid in inaugural.fileids()

for word in inaugural.words(fileid)

for target in targets

if word.lower().startswith(target))

cfd.plot()

Task 1: See how the plot changes when choosing different target words.

Key

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12, 9) targets=['god','work'] cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist((target, fileid[:4]) for fileid in inaugural.fileids() for word in inaugural.words(fileid) for target in targets if word.lower().startswith(target)) cfd.plot()Task 2: See how the plot changes when choosing different target words.

Key

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12, 9) targets=['men', 'women'] cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist((target, fileid[:4]) for fileid in inaugural.fileids() for word in inaugural.words(fileid) for target in targets if word.lower().startswith(target)) cfd.plot()

Collocations

Keypoints:

- We can use NLTK’s

BigramAssocMeasures()andBigramCollocationFinderto find the words commonly found together in a document set. - We can score collocations using

bigram_measures.likelihood_ratio.

We may want to see what terms are often used together. We can do this by looking for collocations in a text, i.e. two word tokens occurring together in the text more often than would be expected by chance.

For this we need to import the nltk.collocations module and more specifically BigramAssocMeasures() and BigramCollocationFinder. We allow a window of 5 words between collocated words.

from nltk.collocations import BigramAssocMeasures

from nltk.collocations import BigramCollocationFinder

bigram_measures = BigramAssocMeasures()

finder = BigramCollocationFinder.from_words(inaugural_tokens, 5)

We then look for words that appear together 10 times or more.

finder.apply_freq_filter(10)

A number of measures are available to score collocations or other associations including bigram_measures.likelihood_ratio. We apply this measure below and show the top ten collocated tokens (occuring in a window of 5 tokens with a frequency of 10 or more).

finder.nbest(bigram_measures.likelihood_ratio, 10)

[('the', 'of'),

("'", 's'),

('.', 'The'),

('.', 'We'),

('United', 'States'),

('has', 'been'),

('.', '.'),

('have', 'been'),

('.', 'It'),

(',', 'and')]

Task: Change the code above to display collocations in the inaugural speeches after stopwords, punctuation and single digits have been removed.

Key

nltk.download('stopwords') from nltk.corpus import stopwords remove_these = set(stopwords.words('english') + list(string.punctuation) + list(string.digits)) bigram_measures = BigramAssocMeasures() filtered_text = [w for w in inaugural_tokens if not w in remove_these] finder = BigramCollocationFinder.from_words(filtered_text, 5) finder.apply_freq_filter(10) finder.nbest(bigram_measures.likelihood_ratio, 7)[('United', 'States'), ('fellow', 'citizens'), ('let', 'us'), ('one', 'another'), ('I', 'shall'), ('Let', 'us'), ('men', 'women')]

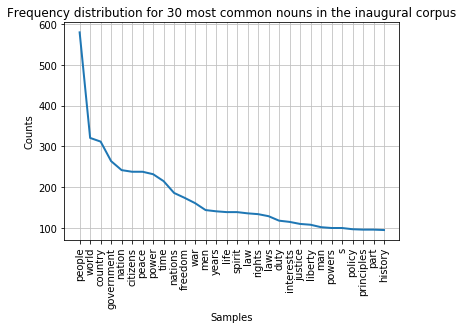

Part-of-Speech Tagging Text

Keypoints:

- We can use a NLTK’s part-of-speech tagger,

averaged_perceptron_tagger, to label each word with part of speech (POS), tense, number, (plural/singular) and case. - We can extract all nouns from a corpus both plural (NNS) and singular (NN).

- We can visualise the nouns from a corpus using a plot of frequence distribution and a word cloud. We can do the same for other POS.

In text mining it can be useful to extract words that have a particular part of speech (POS) such as a noun or a verb. For example extracting all proper nouns can give use names and locations. This is done using a POS-tagger. The POS-tag of a word is a label of the word indicating its part of speech as well as grammatical categories such as tense, number (plural/singular) and case. POS tagging is the process of automatically determining the POS-tags of the tokens in a corpus.

In this lesson, we will use NLTK’s averaged_perceptron_tagger as the POS-tagger. It uses the perceptron algorithm to predict which POS-tag is most likely given the word. We need to download the tagger in order to use it.

The POS-tagger outputs tokens tagged with their POS-tag. It uses the Penn Treebank POS tagset which is widely used for POS-tagging text.

POS-tagging text is very useful when analysing a corpus or document and will allow us to do more indepth analysis and visualisations. In order to pos-tag using NLTK, you also have to import pos_tag from the tag package.

We are going to use the text from the US Presidential Inaugaral speeches.

nltk.download('averaged_perceptron_tagger')

from nltk.tag import pos_tag

[nltk_data] Downloading package averaged_perceptron_tagger to

[nltk_data] /Users/<USERNAME>/nltk_data...

This corpus comes in raw format but also pre-tokenised. Therefore we can call the words() method to retrieve the tokenised text of all speeches.

inaugural_tokens=inaugural.words()

print(inaugural_tokens)

['Fellow', '-', 'Citizens', 'of', 'the', 'Senate', ...]

We can assign POS-tags to all speeches using NLTK’s pos_tag() method and view the first 20:

tagged_inaugural_tokens = nltk.pos_tag(inaugural_tokens)

tagged_inaugural_tokens[:20]

[('Fellow', 'NNP'),

('-', ':'),

('Citizens', 'NNS'),

('of', 'IN'),

('the', 'DT'),

('Senate', 'NNP'),

('and', 'CC'),

('of', 'IN'),

('the', 'DT'),

('House', 'NNP'),

('of', 'IN'),

('Representatives', 'NNPS'),

(':', ':'),

('Among', 'IN'),

('the', 'DT'),

('vicissitudes', 'NNS'),

('incident', 'NN'),

('to', 'TO'),

('life', 'NN'),

('no', 'DT')]

We can then set up lists to hold specific parts of speech such as nouns. Firstly we set up an empty list and then we search for the nouns, NN singular and NNS plural. We can then print the first 20:

nouns = []

nouns = [word for (word, pos) in tagged_inaugural_tokens if (pos == 'NN' or pos == 'NNS')]

nouns[:20]

['Citizens',

'vicissitudes',

'incident',

'life',

'event',

'anxieties',

'notification',

'order',

'day',

'month',

'hand',

'Country',

'voice',

'veneration',

'love',

'retreat',

'predilection',

'flattering',

'hopes',

'decision']

Now that we have created this list of nouns, we can plot their counts in the corpus as we did earlier (see lesson on frequency counts).

from nltk.probability import FreqDist

fdist = FreqDist(nouns)

fdist.plot(30,title='Frequency distribution for 30 most common nouns in the inaugural corpus')

We can also plot the nouns as a word cloud like we did earlier (see lesson on counting tokens in text):

from wordcloud import WordCloud

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

cloud = WordCloud(max_font_size=60,colormap="hsv").generate(' '.join(nouns))

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (16,12)

plt.imshow(cloud, interpolation='bilinear')

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

Task 1: Change the code above to create a frequency list for the most common adjectives in the inaugural corpus.

The POS-tag for adjective ‘JJ’.

Key

adjectives = [] adjectives = [word for (word, pos) in tagged_inaugural_tokens if (pos == 'JJ')] adjectives[:20]

Task 2: Plot a word cloud of the adjectives in the inaugural corpus.

Key

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt cloud = WordCloud(max_font_size=60,colormap="hsv").generate(' '.join(adjectives)) plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (16,12) plt.imshow(cloud, interpolation='bilinear') plt.axis('off') plt.show()

Task 3: You can do the same for another POS-tag.

For the full list of Penn Treebank POS tags see here.

Key

adverbs = [] adverbs = [word for (word, pos) in tagged_inaugural_tokens if (pos == 'RB')] adverbs[:20] import matplotlib.pyplot as plt cloud = WordCloud(max_font_size=60,colormap="hsv").generate(' '.join(adverbs)) plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (16,12) plt.imshow(cloud, interpolation='bilinear') plt.axis('off') plt.show()

Task 4: You can look at the tokens and tagged tokens of individual inaugurals using the fileids() method.

We find the tokens of Biden’s inaugural and Trump’s inaugural, for instace, with the fileids() method, beginning with the most recent, as follows:

inaugural_tokens_biden = inaugural.words(inaugural.fileids()[0:-1])inaugural_tokens_trump = inaugural.words(inaugural.fileids()[1:-2])You can sample slices from the two inaugurals as follows:

inaugural_tokens_biden[55:95]inaugural_tokens_trump[55:95]We can look at their tagged tokens like this:

tagged_inaugural_tokens_biden = nltk.pos_tag(inaugural_tokens_biden) tagged_inaugural_tokens_biden[:20]tagged_inaugural_tokens_trump = nltk.pos_tag(inaugural_tokens_trump) tagged_inaugural_tokens_trump[:20]Now you can search for nouns, adjectives, and adverbs in the inaugurals of Biden and Trump separately, and any other inaugural you’d like to look at, the way we have done for the inaugurals as a whole.

Task 5: Define and text mine the speeches of Biden, Trump, Kennedy, or any other inaugural speech.

Define individual inaugural speeches using the

Textclass function of the NLKT package (confer with course section on concordances). For example:biden = nltk.Text(inaugural.words('2021-Biden.txt'))When you have defined an inaugural, you can search for concordances, collocations, and count for lexical diversity in it. See full description of

Textclass functionality at NLKT.Do concordances in the defined inaugural speeches on these terms: “democracy”, “america”, “freedom”.

What other words appear in a similar range of contexts as these terms? We can find out by appending the term similar to the name of the text in question, then inserting the relevant word in parentheses (confer with the NLTK textbook). Search for words that also appear in the context of some of these terms (“democracy”, “america”, “freedom”).

Search for collocations in each speech.

Measuring things: Count vocabulary and unique vocabulary items. Measure the lexical richness, identify long words and find their frequency distributions. You can see the example code to follow in the NLTK textbook.

Compare the results from your searches. Are there any striking findings?

Practice and review with some basic exercises from the Natural Language Toolkit (NLKT)

First, import nltk.book. Recall that this is a collection of texts you can practice your text mining on that accompanies the NLKT textbook. This text collection is already wrapped with the Text class that supports a variety of exploration, e.g. concordancing, counting, and collocation discovery.

from nltk.book import *

See what texts are imported. You can search for concordances in them.

text1.concordance('monstrous')

text2.concordance('monstrous')

Your Turn: Try searching for other words and in some of the other texts included in nltk.book. For example, search Sense and Sensibility for the word affection, using text2.concordance('affection'). Search the book of Genesis to find out how long some people lived, using text3.concordance('lived'). You could look at text4, the Inaugural Address Corpus, to see examples of English going back to 1789, and search for words like nation, terror, god to see how these words have been used differently over time. Included is also text5, the NPS Chat Corpus: search this for unconventional words like im, ur, lol.

text3.concordance('lived')

A concordance permits us to see words in context. For example, we saw that monstrous occurred in contexts such as the __ pictures and a __ size . What other words appear in a similar range of contexts? We can find out by appending the term similar to the name of the text in question, then inserting the relevant word in parentheses.

text1.similar('monstrous')

text2.similar('monstrous')

The term common_contexts allows us to examine just the contexts that are shared by two or more words, such as monstrous and very. We have to enclose these words by square brackets as well as parentheses, and separate them with a comma:

text2.common_contexts(['monstrous', 'very'])

Your Turn: Pick another pair of words and compare their usage in two different texts, using the similar() and common_contexts() functions.

We use the term len to get the length of something. Measure the length of some of the texts with len.

len(text3) # book of Genesis

Collocations are essentially just frequent bigrams (word pairs), except that we want to pay more attention to the cases that involve rare words and ignore stopwords. In particular, we want to find bigrams that occur more often than we would expect based on the frequency of the individual words. The collocations() function does this for us.

text4.collocations() # inaugurals

text8.collocations() # personals

We have the option to specify measures for exactly how collocations are scored and retrieved as we saw in our section on collocations.